by Gesshin Claire Greenwood

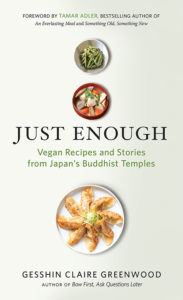

When Gesshin Claire Greenwood was twenty-two and fresh out of college, she found her way to a Buddhist monastery in Japan and soon she was ordained as a Buddhist nun. While at the monastery, she discovered she had a particular affinity for working in the kitchen, especially at the practice of using what was at hand to create delicious, satisfying meals. Her book, Just Enough: Vegan Recipes and Stories from Japan’s Buddhist Temples is based on the philosophy of oryoki, or “just enough.” From perfect rice, potatoes, and broths to hearty stews, colorful stir-fry dishes, hot and cold noodles, and delicate sorbets, Greenwood shows how food can be a direct, daily way to understand Zen practice. With her eloquent prose, she takes readers into monasteries, markets, messy kitchens, and four a.m. meditation rooms while simultaneously offering food for thought that nourishes and delights the body, mind, and spirit.

We hope you enjoy this excerpt from Just Enough: Vegan Recipes and Stories from Japan’s Buddhist Temples

A Zen riddle I often think about asks, “How can you drink tea from an empty cup?” I remember asking a monk in Japan this question. He smiled and said, “Empty cup is better than full cup, because you can always add to an empty cup.” The odd paradox of using less is that sometimes it makes us feel even more satisfied. Becoming comfortable with lack can make us feel as though we have enough.

In my late twenties, I found myself in charge of running the kitchen at a Japanese convent called Aichi Nisodo, where I had lived for three years. I had come to Japan as a young, idealistic spiritual seeker and was hastily ordained in the Soto Zen tradition at age twenty-four — a decision I thought might help me solve my emotional problems (more on that later).

The first time I worked in the kitchen I was taught the basics. I learned how to wash rice, how to make Japanese soup, how to roast and grind gomasio (sesame salt). I spent hours cutting nori (dried seaweed) into thin strips to use as garnish, seeding pickled plums, and picking stones out of raw rice.

Becoming proficient at cooking Japanese food was like adjusting the lens of a camera; it was a process of subtle focusing and readjustment. The biggest shift I had to make was in my relationship to flavor, especially soy sauce. As an American I had poured soy sauce onto rice, but I soon learned that Japanese food uses only a small amount of soy sauce. In Japan, good soup stock, timing, vegetable slicing, and salt, rather than bold flavors, inform the production of a good meal.

I approached learning to cook Japanese food with all guns blazing and no real understanding of the difference between Japanese, Chinese, and Korean food. I was used to dumping soy sauce and ginger onto everything. The first step in learning to cook Japanese food was listening — the willingness to learn. The second step was dialing back my natural impulse to overflavor things. I came to understand that if all steps in a meal are made with care and effort, a little soy sauce goes a long, long way.

In contemporary Western culture we don’t pay much attention to that point in time when we have just enough. We’re conditioned to think in terms of lack. Do I have enough money to retire? Enough friends? Am I exercising enough? This of course is not about having just enough, but about having not enough. We are usually making an assumption based on a comparison with the people around us. How much money we need to retire is relative; it depends entirely on what standard of living we’re used to and what lifestyle we want to maintain. There’s no such thing as too few or too many friends. Any idea about this would come from comparing our number to the perceived friend count of others. And of course, although everyone benefits from exercise, there’s no predetermined universal amount that is sufficient for everyone.

The strange part about this kind of “not enough” thinking is that it usually results in overabundance or excess rather than just enough. Worldwide, the United States has the highest rate of consumer spending per household, the highest military spending budget, and the highest rate of obesity. We have 5 percent of the world’s population, but use 23 percent of the world’s coal. A recent study by Oregon State University indicated that for a woman in the United States, not having a child decreases her carbon footprint by twenty times that of other options like recycling or using energy-efficient household appliances. This is because living in the United States comes with a higher rate of resource consumption. I find this research fascinating; the best thing for an American to do for the environment is to not produce any more Americans.

What’s more, in our culture, success is synonymous with not just the ability to make money, but the ability to buy the right things at the right time. And yet anyone who has felt the emotional toll of earning and spending knows that there is only limited happiness to be found in purchasing the right thing. This is not to say that there’s no pleasure in buying things — of course there is!

There is indeed a kind of aliveness that comes with wanting, but remaining balanced and moderate with desire is easier said than done. What Buddhist philosophy and practice point to is the understanding that our desires are insatiable — that there is never an end to what we want to be, have, buy, or accomplish.

And yet it’s too simple to say, “Wanting is bad.” I was ordained as a Buddhist nun when I was twenty-four years old and spent most of my twenties in monasteries in Japan. At first I was attracted to Buddhism because of the meditation practice; it offered me a sense of calm and sanity in the midst of my stressful, chaotic college years. Soon I came to admire Buddhism’s sophisticated ethical system and the emphasis on simplicity and minimalism. As someone raised in a well-off family, I found the notion of not having or going without revolutionary. However, my time in the monasteries in Japan taught me that Buddhism is not simply about going without, minimalism, or scarcity. It stresses what the Buddha called the “middle way,” a lifestyle between deprivation and excess.

According to legend, the Buddha was a prince, born into a royal family. Trying to shield him from reality, the Buddha’s father gave him everything he wanted: fine clothing, the best food, and beautiful women. However, one day the Buddha left the palace and saw around him sickness, old age, and death. He was then inspired to understand the truth, and he left the palace in search of the end of suffering. For seven years he practiced meditation and asceticism, eating only one grain of rice a day. Due to this severe lifestyle, he became frail and sick and almost died. Luckily, a girl from a nearby village saw him and offered him a bowl of milk. Although in the past he had sworn off milk and other rich foods, at this moment the Buddha drank the milk and felt reenergized. With his newfound strength, he was able to sit and watch his mind long enough to come to understand the causes and conditions of suffering.

This story is the first example of the “middle way.” Initially, the Buddha was a prince. He had everything he wanted and more — excessive amounts of food and riches — but still he was not happy. I think the story of the Buddha appeals to people in developed countries because, if we have our basic needs met, we often are in the same predicament. Trying to counteract this excess, the Buddha fasted and became sick. However, only when he found a middle way between extreme wealth and poverty, between sensual pleasure and self-mortification, was he able to end his suffering. This story can be important guidance for us.

A few years ago I read of a study by Princeton University that showed that money does buy happiness, but only up to a certain point. Researchers found that people who made below $75,000 per year felt more stressed and weighed down by everyday problems and that for those approaching the $75,000 per year mark these feelings lessened. However, making more than $75,000 per year did not make people feel happier. In other words, having enough food, objects, and money does make us feel better, but having more than enough doesn’t.

What if we could retrain ourselves to think in terms of “just enough” rather than “not enough”? And what is this $75,000 amount per year about? For someone in a developed country, $75,000 might be just enough, but for the majority of the world’s population, this amount of money is a fortune. In other words, our sense of what is “just enough” depends in large part on our surroundings, on what we are used to and expect. For some Westerners, finding the sweet spot of “just enough” will mean scaling down.

For Americans, experiencing “just enough” when we eat will often mean preferring the riddle’s “empty cup” by eating less. But I believe this can — and should — be done with joy, grace, and pleasure. There is a beauty in just the right amount of anything: too much furniture in a room gives it a cluttered feeling, but not enough furniture means you can’t sit down. This is not some kind of mystical Eastern concept either! All good painters know the importance of negative space — the artist Kara Walker’s paintings are famous exercises in negative space, and what would Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring be without that black background? With regard to food, there are ways to eat and cook that bring us closer to this philosophy of “just enough.”

But beyond food, I am also interested in what “just enough” means more broadly, what it means to live a life that is sane and balanced, a life that does not devolve into extremes. This interest, of course, arose out of my personal experience living a comfortable childhood followed by a monastic life for many years that was austere and characterized by extreme self-denial. Coming out of that experience of extremes, I knew that, though the strict monastic path was beautiful and stressed many useful and important things, I wanted to find a more radical kind of balance.

Gesshin Claire Greenwood is the author of Just Enough and Bow First, Ask Questions Later. She also writes the popular blog That’s So Zen. Ordained as a Buddhist nun in Japan by Seido Suzuki Roshi in 2010, she received her dharma transmission (authorization to teach) in 2015. She returned to the United States in 2016 to complete her master’s degree in East Asian Studies. A popular meditation teacher, she lives in San Francisco, California. Find out more about her work at Gesshin.net.

Excerpted from the book Just Enough. Copyright ©2019 by Gesshin Claire Greenwood. Printed with permission from New World Library.